Aurore Julien, University of East London

The warmer it gets, the more people crank up the air conditioning (AC). In fact, AC is booming in nations across the world: it’s predicted that around two thirds of the world’s households could have an air conditioner by 2050, and the demand for energy to cool buildings will triple.

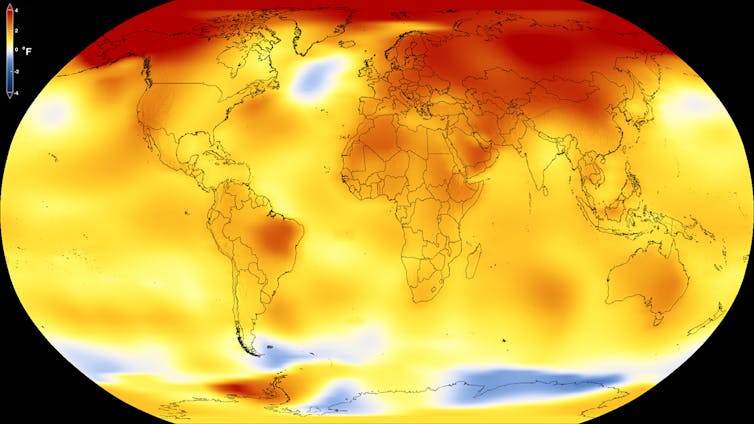

But unless the energy comes from renewable sources, all that added demand will generate more greenhouse gas emissions, which contribute to global warming – and of course, to hotter summers. It’s a vicious cycle – but buildings can be designed to keep the heat out, without contributing to climate change.

1. Windows and shading

Opening windows is a common way people try to cool buildings – but air inside will be just as hot as outside. In fact, the simplest way to keep the heat out is with good insulation and well-positioned windows. Since the sun is high in summer, external horizontal shading such as overhangs and louvres are really effective.

Sometimes it’s better to shut out the heat.

Shutterstock.

East and west facing windows are more difficult to shade. Blinds and curtains are not great as they block the view and daylight, and if they are positioned inside the window, the heat actually enters the building. For this reason, external shutters – like those often seen on old buildings in France and Italy – are preferable.

2. Paints and glazes

It’s now common for roofs to be painted with special pigments that are designed to reflect solar radiation – not just in the visible range of light, but also the infrared spectrum. These can reduce surface temperatures by more than 10°C, compared to conventional paint. High performance solar glazing on windows also help, with coatings that are “spectrally selective”, which means they keep the sun’s heat outside but let daylight in.

There’s also photochromic glazing, that changes transparency depending on the intensity of the light (like some sunglasses) and thermochromic glazing, that becomes darker when it is hot, which can also help. Even thermochromic paints, which absorb light and heat when it’s cold, and reflect it when it’s hot, are being developed.

3. Building materials

Buildings which are made of stone, bricks or concrete, or embedded into the ground, can feel cooler thanks to the high “thermal mass” of these materials – that is, their ability to absorb and release heat slowly, thereby smoothing temperatures over time, making daytime cooler and night time warmer. If you have ever visited a stone church in the middle of the Italian summer, you will probably have felt this cooling effect in action.

Cooler inside than out.

Blaster/Flickr., CC BY-NC-ND

Unfortunately, modern buildings often have little thermal mass, or materials with high thermal mass are covered with plasterboard and carpets. Timber is also increasingly used in construction, and while making buildings out of timber generally has lower environmental impacts, its thermal mass is horrendous.

4. Hybrid and phase change materials

While concrete has a high thermal mass, it’s extremely energy intensive to produce: 8% to 10% of the world’s carbon dioxide (CO₂) emissions come from cement. Alternatives such as hybrid systems, composed of timber together with concrete, are increasingly being used in construction, and can help reduce environmental impacts, while also providing the desired thermal mass.

Another, more exciting solution is phase change materials (PCMs). These remarkable materials are able to store or release energy in the form of latent heat, as the material changes phase. So when it’s cold, the substance changes to solid phase (it freezes), and releases heat. When it becomes liquid again, the material absorbs heat, providing a cooling effect.

PCMs can have even greater thermal mass than stones or concrete – research has found that these materials can reduce the internal temperatures by up to 5°C. If added to a building with AC, they can reduce electricity consumption from cooling by 30%.

PCMs have been hailed as a very promising technology by researchers, and are available commercially – often in ceiling tiles and wall panels. Alas, the manufacture of PCMs is still energy intensive. But some PCMs can cause a quarter of the CO₂ emissions that others do, so choosing the correct product is key. And manufacturing processes should become more efficient over time, making PCMs increasingly worthwhile.

5. Water evaporation

Water absorbs heat and evaporates, and as it rises, it pushes cooler air downwards. This simple phenomenon has led to the development of cooling systems, which make use of water and natural ventilation to reduce the temperature indoors. Techniques used to evaporate water include using sprayers, atomizing nozzles (to create a mist), wet pads or porous materials, such as ceramic evaporators filled with water.

The water can be evaporated in towers, wind catchers or double skin walls – any feature which creates a channel where hot air and water vapour can rise, while cool air sinks. Such systems can be really effective, as long as the weather is relatively dry and the system is controlled carefully – temperatures as low as 14°C to 16°C have been reported in several buildings.

But before we get too enthusiastic about all these new technologies, let’s go back to basics. A simple way to ensure AC doesn’t contribute to global warming is to power it with renewables – in the hot weather, solar energy seems the obvious choice, but it takes money and space. The fact remains, buildings can no longer be designed without considering how they respond to heat – glass skyscrapers, for example, should become obsolete. Instead, well insulated roofs and walls are crucial in very hot weather.

Read more:

Glass skyscrapers: a great environmental folly that could have been avoided

Everything that uses electricity in buildings should be as energy efficient as possible. Lighting, computers, dishwashers and televisions all use electricity, and inevitably produce some heat – these should be switched off when not in use. That way, we can all keep as cool as possible, all summer long.

Aurore Julien, Senior Lecturer in Environmental Design, University of East London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.